In my life so far, I’ve never really uprooted myself from Singapore. Sure, I spent three months in Istanbul (still the city with the best sunsets I’ve seen in my life), but that was on a summer exchange while at university. This was the first time I had to actually think about things like finding a house, renting, making friends and familiarising myself with the city.

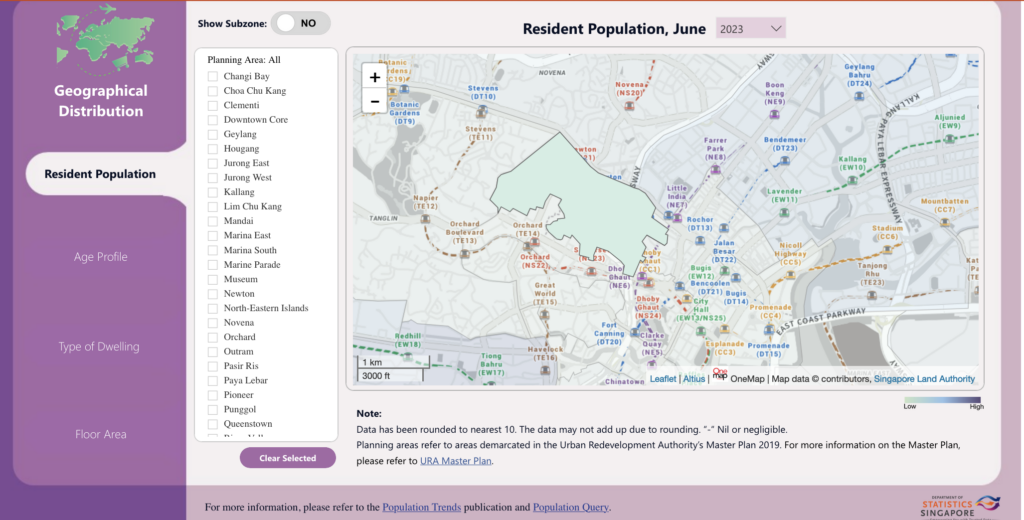

Well I say city, but Matamata feels more like a town. With a population of roughly over 9,000, it is in the Waikato region of NZ and just about 15 minutes from Hobbiton (for my Singaporean friends, Matamata has a population similar to the Newton Planning Area, reference below).

What stood out immediately when I got to Matamata was the number of cars. I would later discover that New Zealand had the highest density of cars per capita in the world. The architecture of the town feels aggressively car-centric, where there aren’t many sidewalks for pedestrians. In my first few weeks, I felt fairly self-conscious walking from my house to the town centre, almost like I was doing something wrong. For a country that values sustainability and the environmental protection of its landscapes, there is a strange cognitive dissonance in seeing the voluminous number of petrol and diesel-powered cars everywhere.

Something I like to do when travelling is to check out supermarkets. While it would usually be a minor curiosity on holiday, my jaunt to the shops in Matamata was purposeful. This would determine the type of food I was going to be eating for the next few months. It was quite eye-opening then, when I saw how expensive groceries were. I’m not much of an economist, but my assumption was that food prices should be lower, given how agriculture and food production were sizeable industries here. Coming from a country without four seasons, I also discovered the ‘beauty’ of seasonal pricing. As I arrived in winter, vegetables and fruits were way higher in price, and your best bet is to purchase in-season vegetables, which is a concept that has taken some getting used to.

It seems like people here try to offset this by growing their own vegetables anyway since most residents have their own gardens. But it definitely impacts holiday workers like me, who are mostly transient and reliant on weekly wages to afford food. I often end up buying canned vegetables, lentils, and cheap protein to cook decently healthy meals. Some brief research on this topic points the spike in food prices towards supermarket monopoly and high import costs, which makes me quite grateful to live in Singapore, where we can export food items fairly easily from neighbours like Malaysia and Indonesia. As a noodle enthusiast, I am also frustrated by both the lack of noodle options (the concept of thick, ban mian1-like noodles seems to be non-existent here) and its price. For the first time in my life, I’ve had to say no to the glutton in me who wants to wolf down packets of Indo Mie or Nong Shim for dinner, all carbs and no proteins.

The size and demographic of Matamata also means that the variety of food is limited. As a vegetarian, my relationship with food has largely been one of convenience, where I treat food as a conduit for sustenance. I obviously have my own cravings, but I’m not one to say, travel somewhere mainly to try out a type of food since my diet already makes most of the decision for me. It was then a moment of self-discovery for me to realise how much I missed specific dishes and relied on it for comfort and joy. In one of my first few weeks in Matamata, I drove 45 mins to Hamilton specifically to find a good place to have masala thosai2, and I’d argue that it was one of the best days I’ve had since I moved here.

Still, not all is bad since I have learnt to adapt and there are other advantages. For one, the taste of any dairy product here is miles ahead of anything I’ve had in Singapore. The butter and milk are delicious, and so are the ice-creams. And for all of my qualms on pricing, the vegetables are way fresher and arguably more delicious. You win some, you lose some.

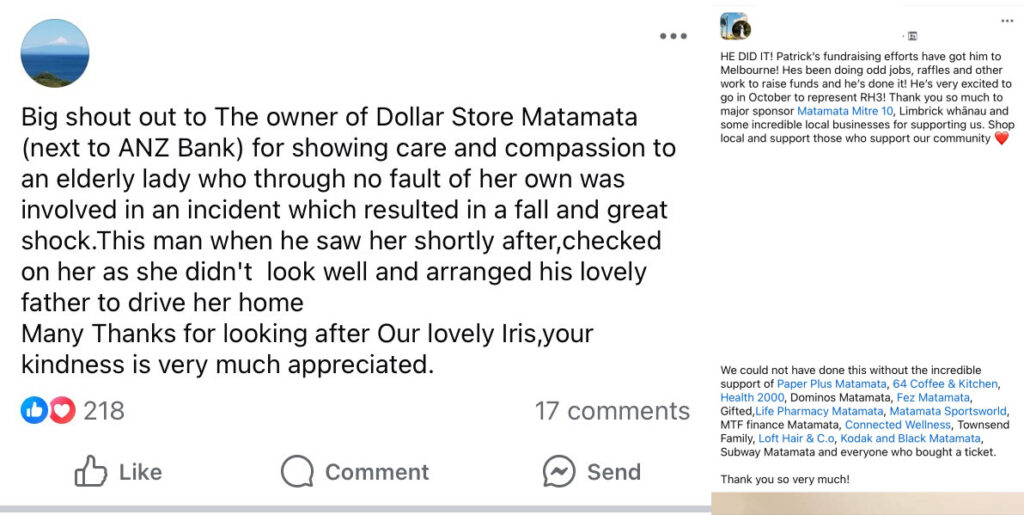

As a town, Matamata is fairly close-knit. There are regular events happening throughout the week, and most residents seem to be familiar with one another. A function of being a small town is that you rely more heavily on the importance of community. There’s even a local Facebook page where people post both updates on happenings in town and offer support to others.

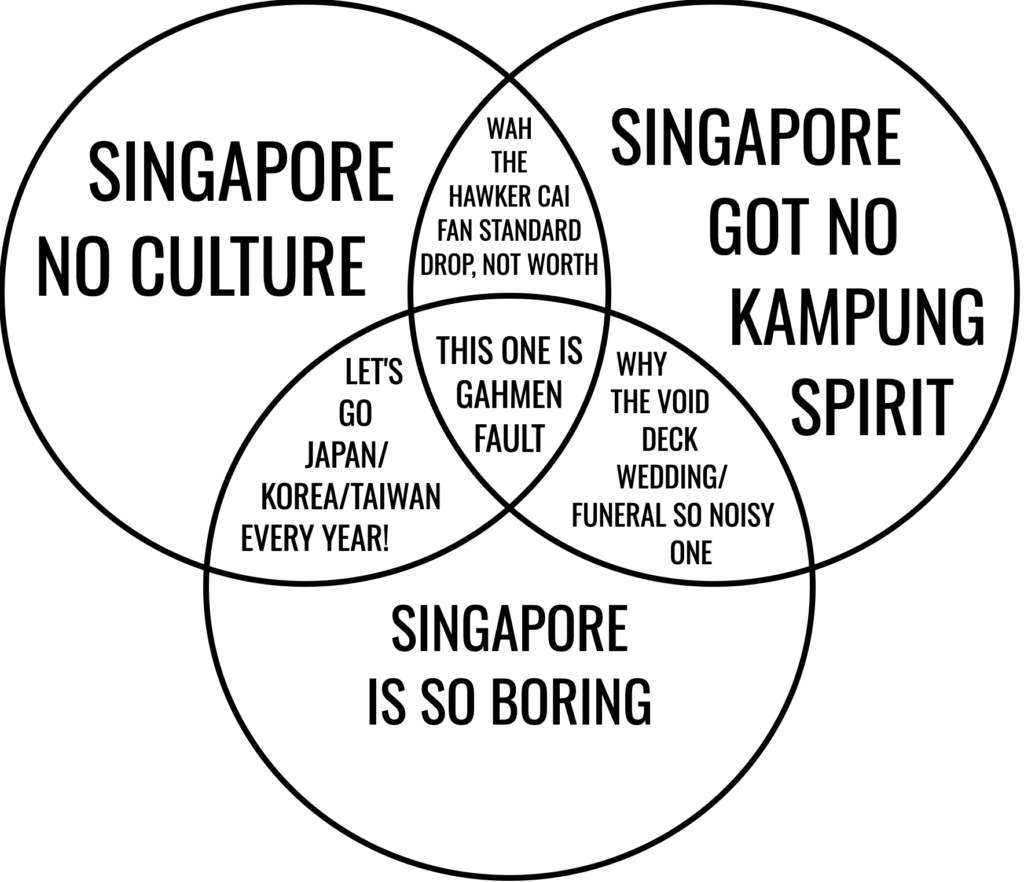

Seeing this warm bond reminds me of a common lament in Singapore about how the mythical kampung spirit3 no longer exists, because people are too busy working, glued on their phones, or living in silo to make friends with their neighbours and foster a sense of community. It is logistically difficult to achieve the initial conception of kampung spirit in Singapore today, because by design we are a crowded country and most people are self-sufficient, so you don’t need to rely heavily on the community to survive. That is starkly different from a town of thousands, where the population size necessitates communal interaction with other residents, positive or not.

I do however find this specific criticism of Singapore to be weak, because there is a lot of community in Singapore; you just have to make an effort to look for it. I feel like there is a variation of the bystander effect at play here, where people want community but will not be the ones to start or take an initiative to join one. It runs parallel to the other oft-cited Singaporean gripe about how we are losing our culture in the form of old-fashioned bookstores and hawker centres (this brings to mind the recent closure of Thambi at Holland Village), but yet people didn’t patronise them when they were alive.

Instead, people are content to moralise, almost to a pessimistic degree about how we can never return to those ‘gold old days’ (imo the kampung sprit ideal itself is heavily tinted in nostalgia, there were many other social and race issues happening concurrently in Singapore in the 60s and 70s). Or better yet, revert to everyone’s favourite pantomime villain, blaming the gahmen4 for the lack of community. This is not to say that governmental policy has not had a sizeable effect on community dynamics and social planning, because it arguably is the biggest factor. But I do feel that there are many organic communities that people form in Singapore which can create these interactions that people seem to be searching for. And we don’t need the government to hold our hand to do it.

I have been guilty of this complaint myself, and before I left for NZ, something I wanted to do was to look for various interest groups that I could join. I joined a book club and started going to more community-led events in my neighbourhood, and it was nice to interact with people of different ages and interests. If anything, my time in Matamata has bolstered my desire to continue seeking out community, especially when I’m back in Singapore.

The other aspect of NZ compared to Singapore which seems to bolster this sense of community is the prevalence of small talk and general friendliness. I’ve not been one for small talk myself, but it has been nice to get into the habit of doing so. Everyone seems to be open to a short chat about how they’re doing or the weather. Even if this type of conversation can be perfunctory, its mere repetition seems to ease people into being more willing to interact with others. I would probably get weird stares if I attempted to ask a stranger about how their day was going in Singapore.

It took me a while to get used to Matamata in general, since I’ve lived in a city all my life where things are easily accessible, efficient and I did not need to integrate into any new communities. It has been a challenge, but one of the best traits of humans is the ability to slowly adapt to the environment over time. I never thought I would live somewhere like this in my life, but it has been an eye-opening experience and I have grown to embrace the quietude and charm of living in such a small town. I will be moving from Matamata in about a month’s time, and some part of me will miss this.

- A type of thicker, handmade noodles created by cutting the noodles with wooden blocks. ↩︎

- A South Indian crepe made of fermented rice and lentil, served with spiced potato curry on the inside. The world always feels full of hope and adventure once I’ve had one of these. ↩︎

- A Singaporean term referring to the sense of community and solidarity found in supporting and interacting with your neighbours. Kampung is a Malay word for “village”. ↩︎

- Singaporean slang, to refer to the government. ↩︎